Managing the Mekong

The Mekong River Basin will change rapidly over the next few decades and by 2025 the population is tipped to rise to between 80 and 100 million.

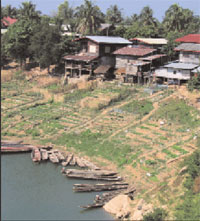

The basin is still in its early stages of development and there is still a high level of poverty. More development is needed if there is to be widescale alleviation of poverty and an increase in the economic welfare of the growing population. This growth is likely to occur in areas such as industry, agriculture, infrastructure and tourism.

However, potential impacts of this development must be carefully monitored and managed if the millions of people who rely on the river for their food and water are to be protected.

For this reason the Mekong River Commission’s Environment Programme is developing a River Health Strategy in order to monitor the health of the river and ensure that development does not cause unacceptable deterioration in the region.

This River Health Strategy is intended to provide a framework for managing the Mekong. Within the framework the governments of the four member countries will be able to work in partnership to make decisions on the management of rivers in the lower Mekong basin. The strategy is also intended to encourage integration of activities within countries, and within the MRC Secretariat.

River health is a term used to describe the ecological condition of a river and it includes a range of physical and biological components that, together, make up the river’s ecosystem.

The River Health Strategy will focus on five main elements which require management if river health is to be maintained. Monitoring procedures are already operating for several of these elements and a newly established monitoring activity is addressing the overall ecological health of the river. These elements are:

Managing the harvest

If too many individuals of any species are removed from the river the species numbers will decline and the species will eventually disappear from the stream. While fish make up the biggest catch from the river, the people of the Mekong also rely on eating snakes, crocodiles, turtles, frogs, insects, riverweed, snails, mussels and more.

In addition to those species that are gathered intentionally, there may be species that are caught unintentionally and killed as by-catch. For example dolphins are no longer killed, but are occasionally trapped in fishing nets and then die. If one species gets wiped out or reduced significantly this can have impacts on the abundance of other species that may have been the food, or competitors with the harvested species.

Managing habitat quality

Fish require quite a complex habitat, not just clean water. Different species require water of suitable depth, and appropriate bottom material and appropriate shelter. They may also need to move to different types of habitats at different times of their life cycles – for example fish moving from deep to shallow waters to spawn, or from the channel to the floodplain to feed; so barriers may disrupt the habitat.

Managing Flow Pattern

The flow pattern of a river plays a key role in regulating the life cycles of the creatures in the river. Many aquatic insects and some fish lay their eggs during the low flow season when eggs are less likely to be washed away. Other fish and aquatic insects reproduce during the high flows when habitat is more abundant. A change in flow for many species seems to trigger migration behaviour. Changes in flow characteristics of the river can interfere with these cues, or reduce breeding success of riverine species.

Managing Water quality

This is the fourth key factor directly impacting the aquatic biota. As water quality deteriorates the number of species that can survive and thrive in a water body decreases. Water quality can be quite difficult to assess, partly because it is often variable in time. Dissolved oxygen is often appreciably lower at night – especially in rivers with high densities of algae. Also toxins and pollutants, such as industrial waste, are also often present in a stream only intermittently, or unexpectedly.

Managing the condition of the catchment

This is indirect, but crucial. The catchment condition influences the amount, timing and quality of the water flowing in to the river. Catchments with large areas of bare soil will contribute to river sedimentation. Intensive agriculture, poorly managed, can lead to excessive nutrients and pesticides contaminating the river. Urban catchments have higher flood peaks and lower base flows because much of the rainfall runs off the paved surfaces directly into the river rather than passing through the soil.

The Environment Programme is developing tools and management programmes to allow the four member countries to cooperate in managing and monitoring all five components.

There are several tool sets required. One is a set of identification keys to allow important components of the all the plant and animal life (the biota) of a region to be identified.

A key to the invertebrates has been completed and is in the final editing process and the programme plans to produce keys to other components of the biota over the next few years. These keys will encourage more research into the classification of basin species and ecology.

The MRC also plans to develop a measuring tool that can be used to quantify river health. At present it has data on the five biological components, but needs to gather more data on chemical changes such as those influenced by nutrients or toxic substances.

Based on biological indicators, the river’s health is considered fairly good. The programme’s goal now is to combine its biological data with the results of the chemical water quality monitoring programme and a diagnostic study that collected data on toxic materials such as pesticides, metals and persistent organic compounds to develop a basin report card.

This card will be widely distributed and easily updated. It can also form the basis for reports which can address a broad range of basin issues, including land use, fisheries and river health.

Choose a newsletter: