Participation has always been an important element of human interaction if not the basic principle of human existence. The origin of today’s debate about participation and civil society can be traced back to the environmental movements in Western Europe and the U.S. in the 1970s and the organisation of civil groups in Eastern Europe in the 1980s. Some elements of the participation process such as mediation procedures were first developed in the United States and later adopted in Europe.

Encouraging the public to participate

The growing awareness about the importance of public participation over the past few years has found its expression in much of the EU legislation and programmes. The 5th and 6th EU Framework Research Programmes, for example, encourage co-operation between inter- and transdisciplinary teams; the EU LEADER+ Initiative aims to involve local people in innovative regional planning. Natura 2000 Process, the Strategic Environmental Assessment and the Environmental Noise Directive, the Aarhus Convention and Local Agenda 21 – all these directives and processes call for active participation of the public. Although public participation per se is a "bottom up" process, its promotion seems to be a "top down" process given that the demands to boost public involvement in decision making processes now obviously come from the highest levels of administration. At the same time that the public is encouraged to participate, it has become increasingly sceptical of large and complex projects and plans. Individual citizens and local initiative groups demand that they be informed and that they be given a say in decision-making processes. In many European countries this has led to a new culture of co-operation in the public sector. The approach behind the EU Water Framework Directive regarding public participation fits very well into this trend.

Eight elements of the culture of participation

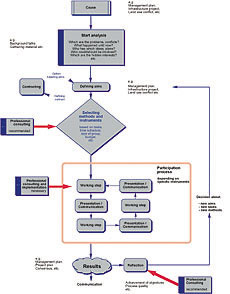

Getting the public to participate requires some change of attitude on the part of individual and group stakeholders. This applies to all three stages in the public participation process, i.e.:

(1) distribution/acquisition of information (e.g. mail, posters, presentations);

(2) consultation (e.g. inquiry, interview, hearing, petition);

(3) active involvement in decision making (e.g. round table, future conference, mediation procedure).

Practical experiences from various participation and mediation projects have enabled eight elements of a culture of participation to be deducted from an example - a case in which a management plan was created in a participatory approach. The eight elements include:

1. Team work

Public participation requires group work. Facilitators who assist bigger

groups to work out a management plan, for example, should work at least

in pairs. This helps to handle critical situations and to reflect on the

process.

2. Roles

Public participation requires clear roles. Who can take part? Who takes

over what mandate? What are the participants' rights and duties? Who will

implement the management plan? Who will do the monitoring? Mixing the roles

causes confusion and might lead to additional conflicts.

3. Appreciation

Each individual is valuable for the process. Lay persons should be viewed

as experts highly qualified on matters concerning their local environment.

Especially in heterogeneous groups composed of e.g. farmers, tourist experts,

water suppliers, energy specialists, administrative bodies etc, the recognition

of the other participants and of other interests is a pre-condition for

good co-operation.

4. Preparation

Public participation calls for detailed preparation. A well-designed process

can help to avoid problems later on. Ignoring the key players or the existing

conflicts or embarking on the process with unrealistic expectations can

lead to a "participation disaster”. Before each step of the elaboration

of a management plan, there should be time to assess the actual situation

and think about different possibilities. Facilitators should always have

a ´strategic reserve´ for critical situations.

5. Agreements

The structure and the rules of the process as well as the expected outcomes

have to be clearly defined from the beginning onwards: how much influence

do the participants have on the contents of the management plan? How will

decisions be made? By whom, how and by when will the plan be implemented?

Who will do the monitoring? If these questions remain unclear, the participants

will accept neither the procedure nor the results of the management plan

and some might even step out of the ongoing process.

6. Questions

Asking questions is much better than "telling the (own) truth´.

It helps to understand other positions, brings different interests forward

and widens the room for negotiation. It is the duty of the facilitators

to ask the right questions and to enable the parties to do the same.

7. Documentation

A complete and clear documentation of the process and of all interim results

helps to avoid potential misunderstandings and serves as the basis for trustful

co-operation.

8. Reflection

Public participation is a permanent learning process. Self-reflection, monitoring

and evaluation are a pre-condition for quality assurance.

Implementing those eight principles does not guarantee immediate success,

but – as several examples in the field of urban, regional and environmental

planning have shown – it does help to make participation work.