|

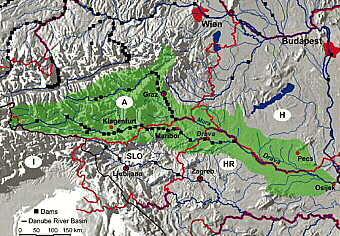

| Map of the Drava from its source to its confluence with the Danube |

For the first 750 km of its course it is a mountain river receiving smaller

tributaries, the most important of which are the Isel (confluence at Lienz,

Austria) and the Gail (Villach, Austria). In its second stretch, from Villach

to Barcs (Hungary), the Drava is turbulent and still fast-flowing, and traffic

is limited to rafts. In this stretch, the river passes through Maribor (Slovenia)

and flows through north Croatia, where it is joined from the northwest by

its largest tributary, the Mura. From shortly after the confluence with

the Mura, the Drava flows 145 km southwest, and forms a large part of the

border between Croatia and Hungary. In its lowest stretch, from Barcs to

its confluence with the Danube (at the border with Yugoslavia), the river

is navigable by small ships. At its confluence with the Danube, the Drava

is 322 m wide.

Over the last century, economic and social pressures on the river have grown

and have been impacted by the changing political and historical conditions

of the countries through which the Drava flows. In Austria, for example,

the pressure that started in the early part of the last century and was

leading to a deterioration of riverine conditions was finally removed and

the situation was reversed by a bold and far-sighted project - the LIFE

Project described below. In the formerly planned economies of the countries

further downstream (Slovenia, Croatia, and Hungary) development along the

river was more measured till the 1990s, but pressure has increased dramatically

since then.

|

| Not all human activities are at odds with nature |

Floodplain restoration in the Upper Drava in Austria

With an average water flow of more than 100 m3 per second, the Drava is

one of Austria’s largest rivers. As a typical Alpine river, it was

once a wild river with side arms, gravel banks, islands, and oxbows. It

hosted large populations of typical fish species such as the Danube salmon,

birds such as the kingfisher and common sandpiper, and other animals such

as the Eurasian otter. Its floodplain area was regularly inundated. Today,

only remnants of the original landscape and species populations exist because

the river has come under increasing pressure from agriculture and housing

since the beginning of the last century; the resulting regulation was systematic,

and considerably changed the river’s character.

The consequence of these decades-long impacts on the Upper Drava was a degradation

of natural freshwater habitats, including alluvial forests, oxbows, and

natural river stretches. In the long term, channelling also deepened the

riverbed by 2cm per year and led to increased flow velocity, which in turn

caused a lowering of the groundwater level. In addition to this, the deterioration

of natural flood-retention capacity increased the risk of flooding.

Because of these problems, the Water Management Authority of Carinthia,

the Austrian province through which the Drava flows, and WWF Austria, developed

a LIFE project to work on a 57 km-long section of the Drava in Carinthia.

Co-financed by the EU and the WWF, this Euro 6.3 million project, which

ran from 1999 to 2002, was one of the largest river restoration projects

in Europe. Its main aims were:

• to maintain and improve (natural) flood protection and the river’s

dynamic processes; and

• to improve the natural habitats and increase the population of typical

species.

The operational strategy was to restore three ecological "core zones”

that cover 7 km of the river. The river bed was to be widened and former

side-arms reconnected in these zones. It was also planned to recreate natural

floodplain forests, protect endangered species, and create a combined biotope

system along the whole valley.

As the project neared completion, new measurements revealed several positive

results. These included:

• better flood prevention. On 200 hectares, natural flood retention

capacity improved by 10 million cubic meters;

• reduced flow velocity, which slows down a flood wave (reduction estimated

at more than one hour);

• recreated natural Alpine and floodplain habitats. Around 50 –

70 ha of islands, gravel banks, steep banks, etc, with their typical species

(Danube salmon, common sandpiper, kingfisher, etc) were recreated;

• stoppage of river bed deepening, and possibly even a raising of the

river bed;

• doubling of certain fish populations, e.g. the greyling.

In effect, this project has shown that river restoration works, and is particularly

good as a strategy to improve flood protection. It is sustainable and cheaper

in the long run; it increases biodiversty and improves the recreation value

of the river for the human population. This is in contrast to river-engineering

measures such as channelisation, or flood protection with dykes, which cause

long-term problems such as river bed deepening and the loss of natural flood

retention capacity. On the Upper Drava, the Water Management Authority of

Carinthia, together with WWF, is working on a "follow up” project

to restore other regulated parts of the river in order to fulfil the objectives

of the WFD.